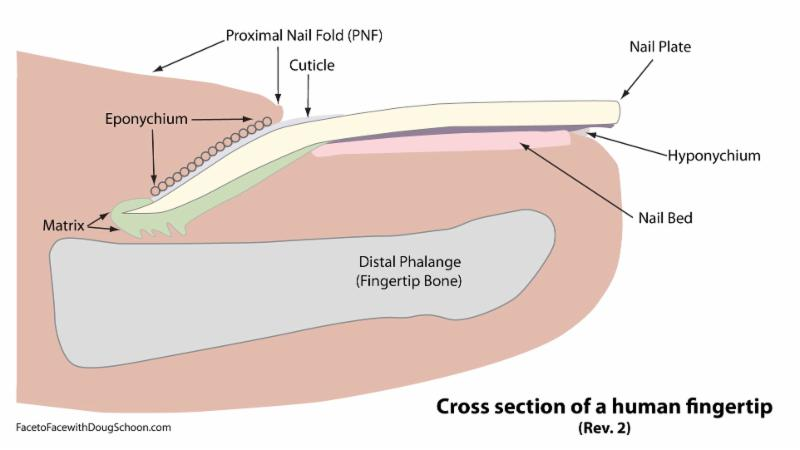

甲床撕裂傷縫合之後. 需要把指甲種回去嗎? 在 Tintinalli教科書有圖片. 如何將甲床種回去. 要精確放入 eponychium 之下. 以保護指甲生長的起點 matrix.

An avulsion or crush injury may tear the nail completely away from the digit or raise a flap of nail bed matrix. Often fragments of matrix tissue may be left on the underside of the avulsed nail; these should be preserved for use as free grafts and, when possible, attached to the nail bed using fine 7-0 absorbable sutures. When the nail or avulsed nail bed fragments are not available, or in the case of a large defect, a full-thickness nail bed graft can be harvested from the patient's toe and sutured into the nail bed of the affected finger. As these injuries are complex and their repair is technically challenging, consultation with a hand or plastic surgeon is appropriate. In addition, avulsion injuries to the nail bed have the poorest prognosis of any fingertip injury. Avulsion injuries may also incompletely tear the proximal portion of the nail bed or the germinal matrix, normally located under the eponychium. When this happens, the germinal matrix may lie on top of the eponychium. Management entails replacement of the matrix into its anatomic position using a series of three horizontal mattress sutures (Fig. 39-3). One suture is placed through the center and one in each corner of the eponychial fold. The sutures are then passed through the proximal portion of the corresponding segment of avulsed germinal matrix and then back out through the nail fold, pulling the matrix back to its anatomic position.

Nail Bed Avulsion Injuries Tintnialli page 322

下面是網路上關於指甲修補的技術圖片.

下面是網路上關於指甲修補的技術圖片.

在uptodate裡面提到. 使用稀釋的優碘清洗指甲. 在中間挖出 3-4 mm 的洞. 可用組織膠將指甲黏回甲床. 但要精確放入 eponychium.

Protect the repaired nail bed by splinting with the original nail, if possible:

•Gently clean the nail in a dilute solution of povidone iodine and normal saline.

•Place a large hole, 3 to 4 mm in diameter, in the center of the nail using a sterile needle, scalpel, or electrocautery to allow drainage.

•Replace the nail beneath the proximal fold (picture 4). The least invasive technique to secure the nail in position is via a tissue adhesive (eg, Dermabond, Surgiseal, Histoacryl Blue, or Periacryl) [13,15]. The nail should be positioned in precise anatomic position by ensuring that the proximal aspect of the nail is underneath the eponychium in order to protect the germinal matrix. Place two to three drops of tissue glue in the areas of the nail folds and allow the stream of adhesive to seal the nail to the skin. Alternatively, the nail plate may be sutured in place through the lateral skin folds with two 4.0 chromic sutures.

Although silicone splints are available, a retrospective analysis of complications after nail splinting with native nail versus silicone nail revealed significantly fewer nail deformities when the native nail was replaced compared with splinting with a silicone product [16].

•If the original nail cannot be used, place a nonadherent splint consisting of a single thickness of nonadherent sterile gauze (eg, Telfa gauze), 0.20 inch reinforced silicon sheeting, or sterile foil from the suture packet in the proximal fold and suture in place through the lateral skin folds using absorbable 4-0 suture or use skin glue (picture 5). There are no comparative studies regarding which of these splinting material results in the best clinical outcomes.

Fingertip and Nailbed Injuries Hand Surgery 1st Edition © 2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Fingertip and Nailbed Injuries (Adam B. Shafritz 手外科醫師 Edward P. Hayes)

A subungual hematoma is the result of some degree of trauma to the nailbed (7). In the event of nailbed injury, primary healing after accurate approximation of the nail matrix is essential for regrowth of a normal-appearing nail (2). Gaps heal by granulation tissue formation, leading to scar and nail deformity or nonadherence. The nail fold, composed of the dorsal roof and the ventral floor, must be maintained by some sort of stent to prevent adherence of the two surfaces by scar tissue. The replaced nail functions best for this purpose. The consequence of nail fold adherence is a split nail or a painful and inflamed nail as the nail cuts through the adhesions.

Distal phalanx fractures usually disrupt the nailbed but may leave the nail plate unaffected (7). A distal phalangeal fracture with palmar angulation combined with a transverse nailbed laceration can deliver the proximal nail plate out of the dorsal nail fold. The Seymour fracture involves a similar nailbed injury occurring with an apex dorsal-angulated Salter-Harris I injury of the distal phalanx (8).

NAILBED INJURIES: NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Options and Indications

Nailbed injuries present with, at the very least, a subungual hematoma. In the event of an intact nail plate and nail margin, the pressure of the hematoma can cause marked throbbing pain. According to Zook and Brown, a subungual hematoma involving at least 25% to 50% of the nail surface area may represent a significant nailbed injury and warrants removal of the nail plate for nailbed inspection and repair (13). A lesser procedure, trephination 甲床穿孔術 of a fingernail and evacuation of the subungual hematoma, can be performed safely with cautery, a heated paper clip, an 18-gauge needle, or an 11-scapel blade.

The traditional teaching mandating nailbed exploration and repair has been challenged in a recent prospective study of childhood fingernail crush injuries randomized into operative and nonoperative treatment groups (14). All patients had a subungual hematoma with an intact nail plate and paronychium and no previous nail abnormality. There was no notable difference in outcome between children treated with nailbed repair and those treated conservatively regardless of hematoma size, presence of fracture, injury mechanism, or age. Monetary charges were substantially higher for the operative group. The authors concluded that nail removal and nailbed exploration is not indicated or justified for children with subungual hematoma, an intact nail, and nail margin.

Authors’ Preferred Treatment and Techniques 如果甲床下的瘀血面積超過 50%. 要考慮合併甲床損傷. 建議移除指甲. 檢查修補甲床.

In the case of a small subungual hematoma (less than 50% of the nail surface area), the authors generally reserve trephination for those patients with moderate to severe pain despite analgesics. For a painful subungual hematoma with an intact nail plate and paronychial tissues and no fracture, trephination using an 11-scapel blade or a 16- to 20-gauge hypodermic needle in a twirling fashion is performed to perforate the nail plate over the hematoma. If more than 50% of the nail is undermined by the hematoma and if a high-energy injury mechanism is involved, consider nail plate removal and nailbed exploration and repair. Often, a stellate and displaced nailbed injury is found under these circumstances.

NAILBED INJURIES: SURGICAL MANAGEMENT 手術時機

Options and Indications 指頭骨折移位. 甲床近端斷裂. 甲床翻出.

Clear indications for surgical intervention are a nailbed injury with associated displaced distal phalangeal fracture, disruption of the dorsal nail fold or other paronychial tissues, or a disrupted or avulsed nail plate.

Results, Review of the Literature, and Factors Affecting Outcome

The standard principles of establishing a sterile surgical field as well as antibiotic and tetanus prophylaxis apply in surgical management of nailbed injuries. For adults, meta-carpal block anesthesia is usually adequate. General anesthesia may be required for children. A blood-free field maintained by a digital tourniquet and the use of loupe magnification are essential for good results (1). Lacerations are repaired after removal of the nail plate. The nail plate is usually quite adherent to the sterile matrix. A careful, atraumatic technique helps avoid iatrogenic injury to the nailbed (7). The use of tenotomy scissors has been described for this process, but a Freer elevator or a small hemostat is a gentler and less risky instrument to introduce under the nail plate for exposure of the sterile matrix.

Aggressive irrigation and débridement are to be avoided; all nailbed tissue should be preserved (1). Reduction and internal fixation of a displaced or unstable distal phalanx fracture should proceed first. If fracture fragments are large enough, Kirschner wire fixation can be used (Fig. 2). Usually, a .028- or .035-in. wire will suffice. If possible, avoid transfixing the DIP joint. Care must be taken to avoid iatrogenic nailbed injury by too dorsal placement of the wire. A nondisplaced or highly comminuted fracture may be adequately stabilized with a combination of soft tissue repair and replacement of the nail plate. Using the replaced nail plate as a native splint after nailbed repair is also effective in restoring stability to open epiphyseal fractures of the distal phalanx in children.

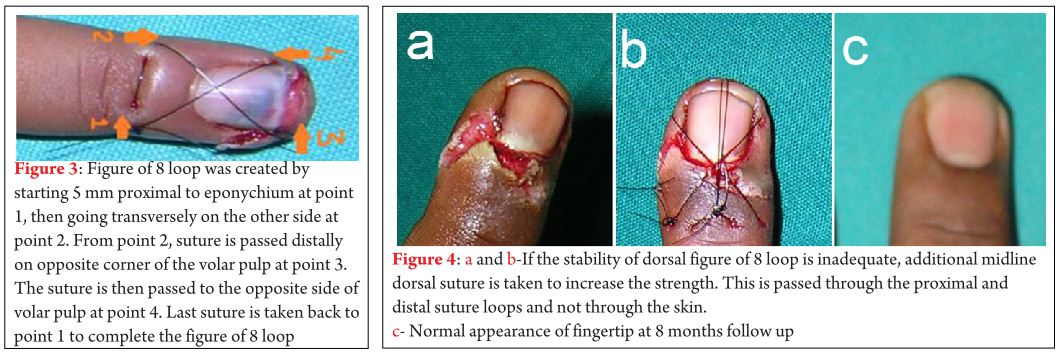

DORSAL TENSION BAND SUTURE 手術三周之後移除縫線.

Supplemental fixation can also be achieved with a dorsal tension band suture placed after nailbed repair and replacement of the nail plate (15). The nonabsorbable monofilament suture is placed proximally in a transverse manner superficial to the germinal matrix through the dorsal nail fold and distally in the opposite transverse direction through the fingertip pulp just distal to the nail. The suture forms a figure-of-eight loop crossing dorsally over the replaced nail. The suture is removed at approximately 3 weeks postoperatively.

如果可以. 將甲床種回去. 可當成骨折的固定器. 保護軟組織. 提供新指甲生長的模板. 避免甲床與 dorsal nail fold 沾黏.

FIGURE 2. Repair of the fingertip and nailbed. The nail plate is gently removed. Unstable fractures of the distal phalanx are reduced and held with a Kirschner wire (K-wire). The nailbed is repaired using fine resorbable suture. Any associated injury to the paronychium and eponychium is also repaired. Pulp injuries are addressed. A drainage hole is placed into the nail plate before reinsertion and fixation with a suture. (Redrawn from Van Beek AL, Kassan MA, Adson MH, et al. Management of acute fingernail injuries. Hand Clin 1990;6:23–38, with permission.)

The best way to achieve a smooth nailbed healed by primary intention is to accurately approximate the edges of lacerations using fine suture (6-0 or 7-0 chromic gut) under magnification (1,2). If the laceration involves the germinal matrix, exposure is obtained by incisions through the dorsal nail fold at perpendicular angles from the eponychial border. These nail fold incisions are also helpful when the proximal nail plate is displaced out of the dorsal nail fold, usually seen with a distal phalangeal fracture or epiphyseal injury and a transverse nailbed laceration. Paronychial lacerations, usually involving the lateral nail folds, should be repaired using 5-0 nylon. Associated injuries of the paronychium and the dorsal nail fold must be meticulously repaired, as they serve as “runners” guiding new nail growth along the appropriate path. If available, the cleaned nail should be placed over the bed and into the nail fold. This additionally splints fractures, protects soft tissue repairs, provides a template for new nail growth, and prevents adhesion formation between the nailbed and the dorsal nail fold.

如果沒有指甲可以種回去. 可使用矽膠片. 或使用縫線包裝的塑膠材料剪成指甲形狀.

Adherent dressings on the raw nailbed are difficult and painful to remove (16). If the nail plate is not available, a silicone sheet or a carefully contoured piece of foil from suture packaging serves the purpose. Replacement of a fractured nail plate repaired with tissue adhesives has also been described (9).

As expected, crush and avulsion injuries, especially those associated with phalangeal fractures, have a worse prognosis than isolated simple and stellate lacerations. Associated injuries to the paronychium and the fingertip pulp also portend a poorer outcome (1). A proximally detached and avulsed germinal matrix is replaced deep to the dorsal nail fold and secured with horizontal mattress sutures tied over the dorsal skin of the nail fold (17). Completely avulsed pieces of sterile or germinal matrix can be sutured into place in the defect directly on the cortex of the distal phalanx. All retrievable pieces of nailbed should be used as grafts, and this includes grafts from unsalvageable digits in severe trauma. In cases of loss of matrix tissue, the nail plate should be inspected for pieces of adherent nailbed. The avulsed tissue can be carefully removed with a scalpel to serve as a graft for repair. When a small fragment of nail plate is adhered to a similar-sized avulsed piece of nailbed, the nail plate along the margins can be trimmed, leaving exposed nailbed, and the composite graft can be sutured to the defect. Shepard reported 85% good results with these techniques of repair of nailbed avulsions (17). The repairs of germinal matrix avulsions were associated with more nail deformity than those of the sterile matrix.

When tissue is not available for repair of defects of the sterile matrix, split thickness nail grafts can be raised from a donor bed (18). The donor site may be from an uninjured portion of the sterile matrix on the affected digit (rarely possible), from an unsalvageable amputated digit, or from the great toe. To avoid a donor site deformity, the graft must be very thin, on the order of seven to ten thousandths of an inch. Expecting some degree of contracture, the graft should be 1 to 2 mm larger than the defect. The longitudinal axis of the graft should be parallel to the defect. The replaced nail plate and an overlying firm dressing are applied. Split-thickness sterile matrix grafts represent a substantial improvement over previous treatments for nailbed tissue loss, including allowing healing with granulation tissue, skin grafts, dermal grafts, reversed dermal grafts, and xenografts.

Loss of the nail plate, nailbed, and periosteum over the exposed distal phalanx can be reconstructed by a split-thickness nailbed graft placed directly on granulating decorticated bone (19). Loss of germinal matrix, provided the defect is not too extensive, can be treated by local rotational or bipedicle flaps (13,17). Local rotation of the full-thickness germinal and sterile matrices on proximally based flaps have been used with success to cover devitalized bone graft to the distal phalanx, a tribute to the robust vascularity of the proximal nailbed. Although the vascular germinal matrix tissues can withstand undermining, they do not advance very far. Larger defects involving greater than one-third of the germinal matrix can be treated with split-thickness germinal matrix grafts from an adjacent area or from the great toe. Split- or full-thickness germinal matrix grafts are not as successful as sterile matrix grafts; both the donor and recipient sites often have some degree of residual deformity. Finally, whole, free, vascularized toenail transfers for reconstruction of congenital and traumatic nailbed defects have been described and, in small series, achieve excellent cosmetic results while maintaining normal hand function (20).

When confronted with loss of dorsal nail fold tissue, the surgeon must remember that the dorsal nail fold has specialized epithelium in direct contact with the nail (1,21). This specialized matrix tissue has some contribution to nail formation and also imparts the shine seen on the nail surface. The contribution of the dorsal nail fold to nail production can sometimes be seen after fingertip amputations when the retained dorsal fold tissues produce painful nail spicules. Reconstruction of tissue loss to the dorsal nail fold is best accomplished with a dorsal rotational skin flap or a reversed cross-finger flap (22). Reconstruction of the specialized matrix of the dorsal nail fold has been successfully achieved using a layer of split-thickness sterile matrix graft sutured to the undersurface of a local rotational skin graft (17).

Authors’ Preferred Treatment, Techniques, Surgical Pearls, and Pitfalls

The described principles of nailbed injury care are commonly used in the authors’ practices. Careful attention to detail in the treatment of these common injuries is suggested. The majority of these procedures can be performed under digital block anesthesia in a well-equipped procedure room. To decrease the risk of subungual contamination and subsequent infections, including osteomyelitis, the affected digit should have a standard surgical scrub before nail removal or trephination. Twenty-four hours of oral antibiotics is generally recommended, but the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics is not proven under these circumstances.

A frequently seen pitfall is iatrogenic injury to the remaining nailbed by too aggressive and impatient removal of the nail plate. After the nailbed repair, we place a small drainage hole in the replaced nail plate to facilitate drainage of any hematoma. The nail plate is sutured proximally deep to the dorsal nail fold and distally to the fingertip pulp with horizontal mattress nylon sutures. The dorsal tension band suture technique is an effective and minimally invasive means of fixation of associated distal phalangeal fractures. Kirschner wire fixation for very unstable fractures is used. Unless there is special concern about tissue viability or infection, the operative dressing is generally left in place for 7 to 10 days. Earlier dressing removal is unnecessarily painful and risks avulsion of the replaced nail plate. Long-term follow-up, on the order of 1 year, is needed to adequately assess and learn from the results of treatment of these injuries. The surgical repair is best reflected in the appearance of the resulting nail plate.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Scar reduction techniques and fingertip desensitization begin roughly 2 weeks from injury, once the wounds have stabilized (7). The replaced nail plate or other stent under the dorsal nail fold will be pushed out by the new nail at 2 to 3 weeks. In the event of no fracture or only a minimal tuft fracture, early range of motion is preferable. Generally, 3 to 4 weeks of protected immobilization of the DIP joint is allowed if there is an unstable distal phalanx fracture. Kirschner wire removal occurs at 4 weeks. A custom fingertip protector can be fashioned to allow early return to work and activities of daily living.

Complications: Etiology, Prevention, Incidence, and Classification

Iatrogenic nailbed deformities have resulted from too vigorous nail plate trephination and removal (9,23). Anatomic repair of a nailbed injury usually results in minimal scar and no significant disruption between the continuum of cells from the nailbed into the nail plate. A wide scar inhibits the cellular continuity over the scarred area and frequently along the entire nailbed distal to the scar. Gaps heal by granulation formation, leading to scar and nail deformity or nonadherence. Distal nonadherence results in loss of the protective hyponychium, leading to the accumulation of foreign material under the nail and predisposing to infection. Proximal nonadherence is even more troublesome, leading to an unstable nail prone to being torn loose. The use of slowly absorbing and large sutures for nailbed repair may cause nail ridging and nonadherence.

Associated distal phalangeal fractures require accurate reduction, as poor alignment of the dorsal cortex leads to nailbed irregularities. Care must also be taken with Kirschner wire placement; superficial wire placement and nailbed injury can lead to longitudinal nail ridging. In the event of distal phalangeal bone loss, care must be taken to ensure adequate distal bone support for the nailbed; otherwise, a hooked or beaked nail can result.

Clinical History, Physical Examination, Office Tests, and Imaging Studies

The distal phalanx must be imaged when faced with nail deformities (24). Nailbed deformities are most often the sequelae of trauma. Malalignment of a distal phalanx fracture or a bone spur commonly leads to nonadherence and other nail deformities. Occasionally, axial cuts of a CT scan through the distal phalanx are beneficial.

Operative Management

Excessive nail matrix scar is the cause of nonadherence. The treatment is excision of the scar (23,24). Closing the defect should not be done under tension and usually necessitates a split-thickness sterile or germinal matrix graft. Malreduced distal phalanx fractures and exostoses commonly lead to nonadherence or ridging of the nail plate. The underlying bone abnormality must be assessed and corrected (Fig. 3).

A longitudinal scar in the germinal or sterile matrices, or both, can cause a split nail plate. The treatment is similar to above with complete excision of the intervening scar (often requiring a microscope) and split-thickness grafting of sterile matrix. More than minimal loss of the germinal matrix requires a local rotational flap, or, more commonly, a germinal matrix graft from the toe. A sterile matrix graft, even if full thickness, will not suffice for a germinal matrix defect.

Adhesions between the dorsal nail fold and the germinal matrix can produce split nails. Reconstructions for loss of tissue or adhesions of the dorsal nail fold must take into account the unique epithelium lining the undersurface of the dorsal nail fold. This tissue assists in nail formation and imparts shine to the nail. Successful reconstructions of split nails have been reported using split-thickness sterile matrix grafts to the undersurface of the dorsal nail fold, coupled with careful postoperative stenting of this space to prevent adhesions.

FIGURE 3. Repair of a ridged and partially nonadherent nail. A: The sterile matrix is exposed. B,C: Scar tissue is excised. D: The distal phalanx is recontoured. E,F: The sterile matrix is repaired primarily and grafted if necessary. (Redrawn from Shepard GH. Nail grafts for reconstruction. Hand Clin 1990;6:79–103, with permission.)

A crooked nail plate curves to one side during longitudinal growth (24). This is caused by sterile matrix scar contracture on one side. After scar excision, the defect requires a full-thickness nail matrix graft. The use of partial-thickness grafts or allowing healing by secondary intention results in excessive contracture and recurrence of the crooked nail deformity.

The hooked nail can result from congenital deficiency of the fingertip, but it most often is a posttraumatic deformity. The usual cause is insufficient bone support of the sterile matrix. A common error in the treatment of fingertip amputations with an associated nailbed injury is to pull the nailbed tissue distally over the exposed distal phalanx. Prevention is the key. Because the shape of the nail plate follows the contour of the nailbed, the nail plate curves palmarly over the fingertip pulp. Healing by secondary intention can allow for significant contracture of the dorsal soft tissues and draw the nailbed distally. The hooked nail deformity can be avoided by ensuring adequate distal bone support of the nailbed and by avoiding tension in re-approximating the dorsal and palmar soft tissues.

The distal edge of the sterile matrix should be at least 2 mm proximal to the distal extent of the distal phalanx bone stock. Two steps may be necessary to address this problem. First is correction of the mismatch between the distal phalanx and the nailbed. Options include shortening the nailbed, releasing the nailbed and allowing it to retract dorsally, and lengthening or osteotomy of the distal phalanx. After correction of the nailbed-bone relationship, soft tissue coverage for the fingertip is needed. Options include advancement of local tissues, full-thickness skin grafts, and regional or distant flaps (25).

Fingertip injuries can include a wide variety of injuries and can be successfully managed by a spectrum of options from simple nonoperative treatments to rather complicated reconstruction techniques. As summarized by Ma et al. (26), regardless of the treatment option chosen and the experience and/or level of training of the treating surgeon, the results of many treatments yield similar good results. This portion of the chapter focuses primarily on both nonoperative treatments of fingertip injuries with or without associated nailbed injuries and simple operative procedures (flaps) on the fingertip.

For fingertip amputations and injuries, a wide variety of classification schemes exist (27,28,29,30,31,32 and 33).

These classification systems are based on amputation level, obliquity, nailbed involvement, and/or bone exposure. A practical simplification divides these injuries into two main categories of amputations and fingertip injuries: those that include skin and/or pulp loss but do not involve exposed bone, and those that involve exposed bone. This simple classification system helps to guide the surgeon’s treatment options and decisions, especially if replantation is not considered to be a viable option.

Nonoperative Treatment: Results and Outcome, Review of the Literature, and Factors Affecting Outcome

Options and Indications

Numerous methods have been devised and reported over the years for nonoperative treatment of pulp and skin loss on the tip of the digit. Usually, nonoperative treatment is recommended for injuries that do not involve exposed bone. The simplest method of nonoperative therapy involves simple mechanical débridement followed by the application of an antibiotic ointment to the fingertip, a nonadherent sterile dressing, tube gauze, and fingertip protector cap. Examples of these nonadherent dressings include OpSite (Smith and Nephew), Xeroform (Sherwood Medical), Adaptic (Johnson and Johnson Medical), Vaseline gauze (Sherwood Medical), and Owens (Davis and Geck).

The results of simple open treatment have been reported with the use of an OpSite dressing (34,35). Mennen and Wiese reported on 200 fingertip injuries treated simply with an OpSite over the injured fingertip after local irrigation and débridement (34). The theory behind the treatment protocol is that a semi-occlusive dressing provides a temporary “skin” that would allow for healing of the underlying soft tissues in an optimal environment, thereby promoting earlier granulation tissue formation and epithelialization of the wound. In their study, the authors found that the use of a simple weekly dressing change of an OpSite resulted in near normal pulp shape and useful epithelium of an injured fingertip within a period of 20 to 30 days. They thought that the dressing should not be changed any more frequently than once per week, as this would slow healing. This method was used regardless of whether bone of the distal phalanx was exposed. They had no complications requiring surgery, and no patients developed a significant hook nail deformity. Patients recovered and regenerated a nearly normal pulp with excellent tactile sensation. In a similar study, Williamson et al. reported favorable results using similar materials on 40 patients (36).

Using a different technique, Fox et al. reported on 18 adults treated nonoperatively with a simple wound cleansing followed by coverage with an occlusive dressing made from sterile aluminum foil and gauze (37). Dressing changes were performed on the third, fifth, and seventh day, and then weekly until the wound healed. They reported that although at 2 weeks into the treatment the wound did not appear aesthetically pleasing, healing of the amputated fingertip occurred within 4 weeks, and the resultant fingertip had excellent sensory perception. Normal digital range of motion was noted, and acceptable cosmetic appearance was the rule. They thought that this outcome was satisfactory to all and resulted in less than 10 days lost from work.

A study by Buckley et al. reviewed the results of patients treated conservatively with silver sulfadiazine dressing changes performed on 21 digits, six of which had exposed bone (38). An occlusive dressing of Vaseline gauze with silver sulfadiazine covered by a finger portion of a disposable rubber glove was fashioned. The dressing was changed every other day during the first week and then on an as-needed basis until healed (range, 19 to 90 days). The cases were reviewed at an interval of 2 to 8 years after injury. All of the patients were satisfied with the treatment and the cosmetic appearance. Complications included minor nail abnormalities in 29% of patients, scar tenderness in 19%, and variable degrees of cold intolerance in 38%. Two-point discrimination was normal in all. All preferred the results obtained versus a revision amputation, digital shortening, and primary closure.

Ipsen et al. reported a prospective investigation of 81 consecutive fingertip injuries in which conservative treatment was used (39). The fingertip injuries were defined as greater than or equal to 1 cm × 2 cm in the distal phalanx without any joint or tendon injuries. All of the wounds were cleansed and covered with simple Vaseline gauze. If bone was exposed, 2 to 3 mm of bone was removed with a rongeur, and the wound was dressed in the same manner. Dressings were changed to fresh Vaseline gauze via soaks on day 5 and then weekly until healed. The average healing time was 25 days, with complications of scar tenderness in 26% of patients, cold intolerance in 36%, and nail deformities in 58%. In a similar study, Lamon et al. studied 25 fingertip amputations treated by débridement and application of bacitracin ointment and simple gauze dressings (40). The dressings were changed after 48 hours and then a three-times daily program of warm soaks in mild soapy water for 10 minutes followed by application of bacitracin and gauze dressing was instituted. This regimen was continued until the wound healed. Exposed bone was present in six cases. The average time to healing was 29 days. Those patients who were able to return to work (those who could keep their fingers clean and dry) were able to do so after 24 hours. Three patients had minimal sensory changes, there were no infections, and there were no significant complications reported with the use of this technique.

The use of Mepitel silicone net dressing (SCA Molnlycke Ltd, Bedfordshire, UK) was recently reported by O’Donovan et al. (41). They compared the silicone dressing to traditional

P.1108

dressings used on fingertip injuries in children ages 6 months to 11 years. During the first 3 weeks of dressing changes, the Mepitel net prevented adherence of the wound to the outer dressing and therefore significantly reduced the pain and anxiety suffered by the children associated with wound care. There was no difference in time of wound healing associated with this method when compared to other methods.

The use of chitin as a biologic dressing for fingertip injury has been reported (42,43). Hyphecan artificial skin membrane (Hainan Kangda Marine Biomedical Corp., China) is an occlusive fingertip dressing made of a chitin derivative (1-4,2-acetamide-deoxy-beta-D-glucan) that is extracted from shellfish exoskeleton. It is nonantigenic and thus does not cause systemic allergic reactions. It is semipermeable and maintains a sterile environment without wound dehydration. The protocol for its use requires a simple local irrigation and débridement and application of the Hyphecan cap and sterile gauze over the cap. The cap is not changed. It is slowly cut away as it dries and separates from the wound as it heals. Excellent results have been reported in 276 fingertip injuries treated in such a manner (42,43). No significant complications were reported, and all patients were satisfied with form and function of the injured finger. No revision surgery was needed in any case.

Finally, Ma et al. (26) reported on the treatment of fingertip injuries using a simple dressing, split-thickness skin grafting, full-thickness skin grafting, V-Y advancement flaps (both Kutler and Atasoy), revision amputation and primary closure, and cross-finger flap. In their series of 200 randomized patients, they found little difference in the ultimate results among any of the methods used.

Authors’ Preferred Method of Treatment

If nonoperative treatment is going to be accepted by the physician and patient, these injuries are easily treated and serially followed until healing is assured. It is probably not appropriate to elect nonoperative treatment if a skin defect larger than 1 cm × 2 cm is present, and/or if there is exposed bone present. The patient is evaluated in the emergency department or office, and a digital block is used to allow for adequate débridement of the fingertip injury in a painless fashion. After adequate débridement is performed, Bactroban ointment (2% Mupirocin ointment, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA) is applied to the wound and covered by Xeroform nonadherent dressing. The finger is then covered with gauze, and a simple fingertip tube–type dressing is applied. A metal cap fingertip protector is placed over the dressing to prevent the patient from inadvertently injuring the finger. This dressing is kept clean and dry until the patient is reevaluated. Mild narcotics and oral antibiotics (cephalexin or clindamycin if patient is allergic to penicillin) are usually prescribed for a short course but have not been shown to affect outcome.

A wound check is performed at 2 or 3 days. The old occlusive dressing can be soaked off in a sterile saline solution. The fingertip is then reevaluated for further demarcation of injury and necrosis. Further débridement may be performed in the office. A repeat application of a similar dressing is then placed, and the patient is examined at weekly intervals with weekly dressing changes. As the wound gradually begins to granulate, the patient can perform dressing changes as necessary at home, unsupervised.

If an adequate débridement cannot be obtained from a single time in the emergency department or office (e.g., if there is grease or other organic matter embedded in the pulp), the patient is referred to the hand therapy unit for sterile whirlpool débridement of the fingertip. This treatment is begun after the patient has been seen for the first follow-up examination and is performed on a daily basis. After each treatment session, the fingertip is dressed with antibiotic ointment, nonadherent dressing, and clean gauze. The patient is reassessed twice weekly until there is evidence of granulation without any evidence of infection. Once this is accomplished, the patient can then be monitored on a weekly basis, and the patient can be instructed on home dressing changes. Depending on size of the involved skin loss and pulp loss, the patient may need to be followed conservatively over 4 to 6 weeks. Many patients need reassurance that the wound will heal and that good results are the rule (Fig. 4).

Surgical Management: Results and Outcome, Review of the Literature, and Factors Affecting Outcome

Options and Indications

If nonoperative therapy is not acceptable to the patient and/or if there is exposed bone with soft tissue and skin loss as well as nailbed injury, then surgical management is considered. Six commonly used methods of acute fingertip reconstruction are reviewed. Four of these procedures can be performed in the emergency department or a well-equipped procedure room. These include the “cap” procedure or composite grafting, the Kutler repair, the Atasoy V-Y advancement flap, and revision amputation and primary closure. The cross-finger flap and thenar flap and its variations are also discussed; however, it is recommended that this operative procedure be performed formally in the operating room. Finally, some special situations and alternative local flaps are reviewed.

“Cap” Technique (Composite Grafting)

The “cap” technique is nonmicrosurgical reattachment of fingertip amputations (6). This method of treatment is effectively used in children and adults who have amputated

P.1109

their fingertip through the mid-level or distal to the nailbed, either by a guillotine-type amputation or by avulsion. The technique can be performed in the setting of a dirty wound that would not be suitable for formal replantation. The procedure requires the presence of the amputated part for reattachment. For young children, it is recommended to proceed to the operating room so that adequate anesthesia and sedation can be achieved. It is important to explain to family members and the patient (if appropriate age) that this procedure is not a true replantation, rather that it is a way of reattaching the amputated part to form a “biologic dressing” or scab. This procedure allows for granulation tissue to form underneath the amputated part as the body naturally heals the fingertip over time. The patient and/or family members must be informed that the replanted part will undergo necrosis and desiccation. Eventually, over the course of 4 to 6 weeks, it will form a scab and fall off, leaving behind a well-healed fingertip. This procedure is quite effective at restoring, overall, a normal looking fingertip. However, this fingertip will not be identical to its uninjured counterparts.

FIGURE 4. A–D: Nonoperative treatment of fingertip injuries. A,B: The photographs demonstrate full-thickness skin and pulp loss to the fingertips as well as exposed bone of the distal phalanx of the thumb, resulting from a blast injury from fireworks. Note the damage to the paronychium and nail fold. Simple dressing changes were performed for 2 months. The results at 2 months are shown in panels C andD.

Operative Procedure

Composite grafting may be performed in the emergency department or in the operating room with digital anesthesia and the use of a finger tourniquet. After adequate débridement of both the injured finger and the recovered fingertip, the nail plate is removed from the amputated part as well as from the digit. If bone is present in the amputated part, it is cleared using a rongeur or a knife. Excess fat and subcutaneous tissue are removed from the

P.1110

amputated part. The skin edges, subcutaneous tissue, and bony end of the finger are débrided. The fingertip and amputated portion are simply sutured using a resorbable stitch such as 6-0 chromic gut (Fig. 5). The nailbed is repaired to itself as well, if possible. Once the portion of the digit has been reattached, sterile dressings are applied after release of the finger tourniquet. Reevaluation occurs at 5 to 7 days.

FIGURE 5. A–D: Composite grafting (“cap” technique). A 2-year-old boy sustained an amputation through the mid-nailbed (A). The wound was grossly contaminated with grease on presentation. After débridement, the fingertip was reattached (B). It underwent necrosis and desiccation as expected (C) and fell off 2 months later. His results at 5 months are shown (D).

The results of this technique were evaluated by Rose et al., and they reported on seven adults treated in this manner (6). They found that this procedure was effective at returning the fingertip to a near-normal appearance, that the mean two-point discrimination was 6.5 mm, and though the finger was shortened an average of 6 mm, it did give the illusion of a normal fingertip. There were no infections, and, overall, satisfactory results were the rule.

Atasoy Volar V-Y Advancement Flap

The Atasoy volar V-Y advancement flap has been attributed to Tranquilli-Leali (44) as described in 1935, but gained its commonly used eponym when Atasoy et al. published their results in 1970 (45). The flap may be used with transverse or dorsal oblique injuries to the fingertip involving both the nailbed and the pulp with exposed bone. It is less useful when a palmar oblique fingertip amputation is encountered. The technique is based on a V-Y full-thickness advancement of the digital pulp over the tip of the finger. It is important when considering this technique to remove any excess or redundant nailbed to avoid the hooked nail deformity. Atasoy et al. reported on their results in 1970 and found that 56 of 61 of patients had near-normal motion and sensibility in their fingertip (45). However, these findings were contradicted by Tupper and Miller when they reported decreased sensibility in 15 of 16 patients and that 50% of patients developed cold intolerance after the Atasoy V-Y flap was performed (46). Three patients had a mild hook nail deformity, and 2 of the 16 patients (12.5%) were dissatisfied with their final results.

Operative Procedure

The Atasoy volar V-Y advancement flap can be performed in the emergency department

P.1111

with a simple digital block and digital tourniquet. After surgical prep and drape, excess sterile matrix is removed 1 to 2 mm proximal to the bone of the distal phalanx. The bone may need to be shortened using a rongeur (Fig. 6). Next, a full-thickness skin flap of digital pulp is brought up, with care not to injure the flexor digitorum profundus attachment and the vascular supply to the flap. The procedure should be carried out with loupe magnification to ensure preservation of the small-caliber vessels supplying the flap during division of the fibrous connections securing the flap. Care must also be taken to avoid crossing the DIP flexion crease; otherwise, a contracture may ensue. The palmar flap is mobilized distally and dorsally, and a nailbed repair directly to the distal edge of the flap is performed using a 6-0 chromic gut suture. The medial and lateral portions of this flap are then sutured to the remaining digital pulp using either an absorbable or nonabsorbable suture (a 4-0 nylon or Prolene stitch is sufficient). Finally, the more proximal portion of the V is closed on itself using this same suture.

Kutler Lateral V-Y Flaps

William Kutler described his procedure of creating two lateral V-Y flaps to close fingertip amputations in 1947 (47). It remains useful in treating transverse amputations of the distal phalanx through the level of the nail and nailbed. Like the Atasoy flap, it can be performed under digital anesthesia in the emergency department. Two simple lateral V-Y advancement flaps are created to meet in the midline of the digit. The procedure is thus suitable for dorsal oblique and transverse amputations, but is less applicable to palmar oblique amputations. This procedure is described below and shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 6. The Atasoy volar V-Y advancement flap. A: The fingertip is débrided, and bone is shortened if necessary. B: A full-thickness triangular palmar flap is developed and advanced to the sterile matrix. The skin is then closed as illustrated (C). [Redrawn from Atasoy E, Ioakimidis E, Kasdan M, et al. Reconstruction of the amputated finger tip with a triangular volar flap. J Bone Joint Surg 1970;52(A):921–926, with permission.]

FIGURE 7. The Kutler lateral V-Y advancement flaps. The fingertip is débrided and bone is shortened if necessary. Two lateral full-thickness flaps are developed and advanced as shown. [Redrawn from Shepard GH. The use of lateral V-Y advancement flaps for fingertip reconstruction. J Hand Surg

沒有留言:

張貼留言